BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

URL: http://imtj.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-3199-en.html

, Masomeh Esmailzade2

, Masomeh Esmailzade2

, Reza Esmaeili3

, Reza Esmaeili3

, Mohammad Matlabi4

, Mohammad Matlabi4

, Ali Ekrami Noghabi5

, Ali Ekrami Noghabi5

, Maryam Saberi *6

, Maryam Saberi *6

2- MSc. in Health Education and Promotion, Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Health, Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Gonabad, Iran.

3- Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health, School of Health, Social Development and Health Promotion Research Center, Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Gonabad, Iran.

4- Associate Professor in Health Education and Promotion, Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Health, Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Gonabad, Iran.

5- PhD. Candidate in English Language Teaching, Students Affairs, Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Gonabad, Iran.

6- Instructor, Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Health, Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Gonabad, Iran. ,

1. Introduction

In recent years, dramatic demographic changes have taken place worldwide, of which the unprecedented decline in fertility rates in many developed and developing countries is one of the important changes [1]. Fertility plays a major role in the quantitative and qualitative transformation of the population in countries [2]. Fertility rate decline initially began in Europe and currently are observed in Asia, especially in East and Southeast Asia. In parallel with these changes, Iran has also undergone extensive changes. The results of the available statistics in Iran show that the total fertility rate of about 7.7 children per woman in 1967 reached 2.17 in 2001, 1.8 in 2007, and 1.6 in 2012 [2, 4]. Given that the overall fertility rate is 2.1 for population replacement, the Iranian population is currently experiencing fertility below the replacement level [5].

Today, the attitude of Iranian families towards childbirth has changed [6]. One of the adverse effects of the “one-child phenomenon” is generation imbalance. Identifying single-parent families is an important part of “population and family planning program” and related interventions [7]. A review of studies on “declining fertility rates” in Iran shows that fertility declines in recent decades have been closely linked to structural modernization factors, family developments, changing in child value, changing in the pattern of reproduction, establishing and expanding family planning programs, improving women’s status and their independence economic factors, and individual characteristics, such as age, educational achievement, etc. [8].

One of the most effective theories of health education in the “fertility intentions” is the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [9]. According to this theory, the most important determinant of a person’s behavior is “behavioral intention”; then a combination of attitudes toward “behavior”, “abstract norms”, and “perceived behavioral control” can lead to a behavior:

A. Attitude towards behavior: The “attitude” means negative or positive personal evaluation about a behavior; in other words, when a person wants to do something, he first evaluates the results and then intends to do it.

B. Abstract norms or social pressures: People are influenced by other people (such as father, mother, wife, religious leaders, family, health workers, etc.) in the society and behave by their influence or under their pressure; in fact, an individual bases his intention on the will of others.

C. Perceived behavioral control: It indicates how much a person feels that his deeds and behaviors, whether positive or negative, are under his/her own control. If a person believes that he/she does not have the resources or opportunities to behave, he is unlikely to have a strong intention to engage in behavior [10].

The aim of this study was to determine the effect of training based on TPB on the fertility intention of single-children women due to the importance of fertility in Iran and the need to identify the factors affecting it.

2. Materials and Methods

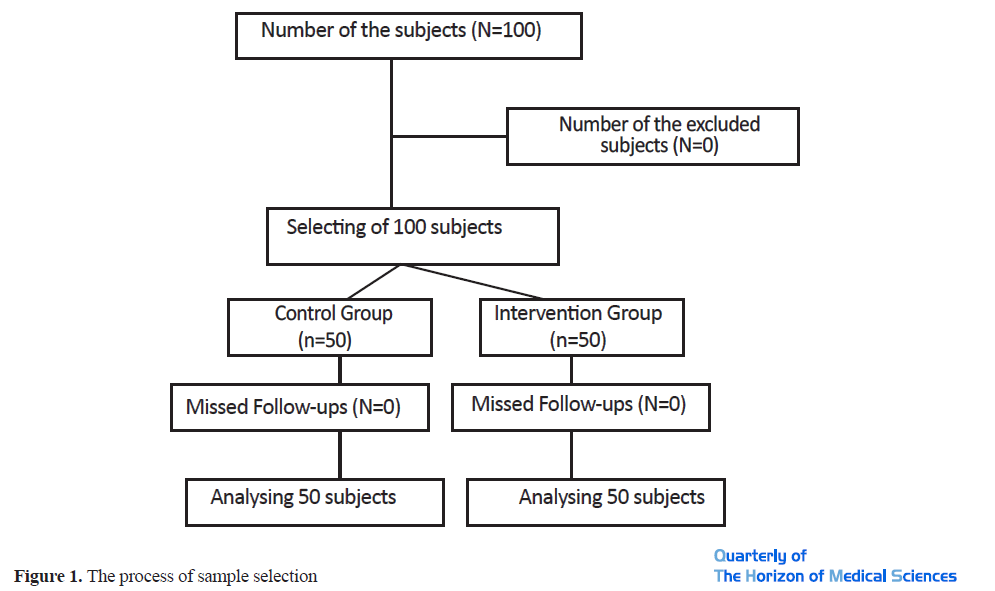

This intervention study was conducted on 100 single-child women living with their husbands covered by two health centers in Gonabad City selected by the two-stage cluster sampling from about 45,000 cases. After preparing the single-child women list from each center, the subjects were divided into two groups of experiment and control (n=50 per group) using the randomized block design. Based on extensive Internet research assessing national and international studies, the most similar and latest study was selected. It should be noted that since no similar intervention study was found on a relatively large scale, a non-interventional study was used to calculate the sample size.

Based on the searching results and advice received from experts in fertility promotion, an intervention can be considered effective, when it can reduce the unwillingness of having children to about 50%. According to the results of a study by Hosseini et al. about 70% of the respondents were reluctant to have the next child [6]. Assuming that the present intervention could reduce this value to 40%, a total of 43 subjects were considered for each group. In order to control possible errors in the process of implementing the interventions, data collection, and analysis, the sample size in each group was considered 50 subjects:

The including criteria were as follows: participants should not be barred from pregnancy, literacy, females of childbearing age, no pregnancy, and having a child of one year or older. Regarding the objectives of the study and the confidentiality of the information, the necessary explanations were given to the control group and they were ensured that they can withdraw the program in case of dissatisfaction and unwillingness to cooperate.

The data collection tool was a researcher-made questionnaire with two sections: the first section included demographic information (age, level of education, occupation, spouse’s age, spouse’s education level, spouse’s job, economic status, age of the child, history of abortion, and history of stillbirth). The second section included TPB constructs (attitude=8 questions, abstract norms=7 questions, perceived behavioral control=7 questions, and behavioral intention=5 questions). The questions were ranked on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 to 5 (I totally agree, I agree, I have no opinion, I disagree, and I totally disagree). In case of full agreement (I totally agree), score 5 and in case of disagreement (I totally disagree), score 1 was given to the relevant question.

To quantify the validity of the content, two indicators of Content Validity Ratio (CVR) and Content Validity Index (CVI) were used. To determine the CVR, 11 specialists in health education, maternal and child health, and epidemiology were asked to review the designed questions of each item on a 3-point scale (necessary, useful but not necessary, and not necessary).

According to Lawshe’s table, to determine the minimum value of the content validity index, the questions whose numerical CVR level was higher than 0.95 based on the evaluation of 11 experts were accepted [11]. Hirkas et al. (2003) recommended a score of 0.79 and higher for accepting items based on a CVI score [12].

To determine the reliability of the questionnaire, two methods of determining internal similarity and stability were used. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (0.96) was used to measure the internal consistency of the questionnaire and the experimental-retest method (2-week interval) and the intra-cluster correlation coefficient (0.94) were used to stabilize the questionnaire [11]. After confirming the validity and reliability of the questionnaire, the educational intervention was performed for the experimental group in 3 45-60-min sessions through lectures, group discussions, educational videos, pamphlets, and textbooks). We focused on the theoretical constructs of TPB of the child, the importance and status of the child from the perspective of Islam and Quranic verses, the benefits of having children, the disadvantages of having one child, and the ways to deal with the problems related to the child.

The questionnaire was re-completed one month after the intervention by the two groups. The SPSS V. 20 software was used to analyze the collected data. The data were first analyzed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, followed by the t-test, paired t-test, and Independent t-test at a significant level of less than 5%.

3. Results

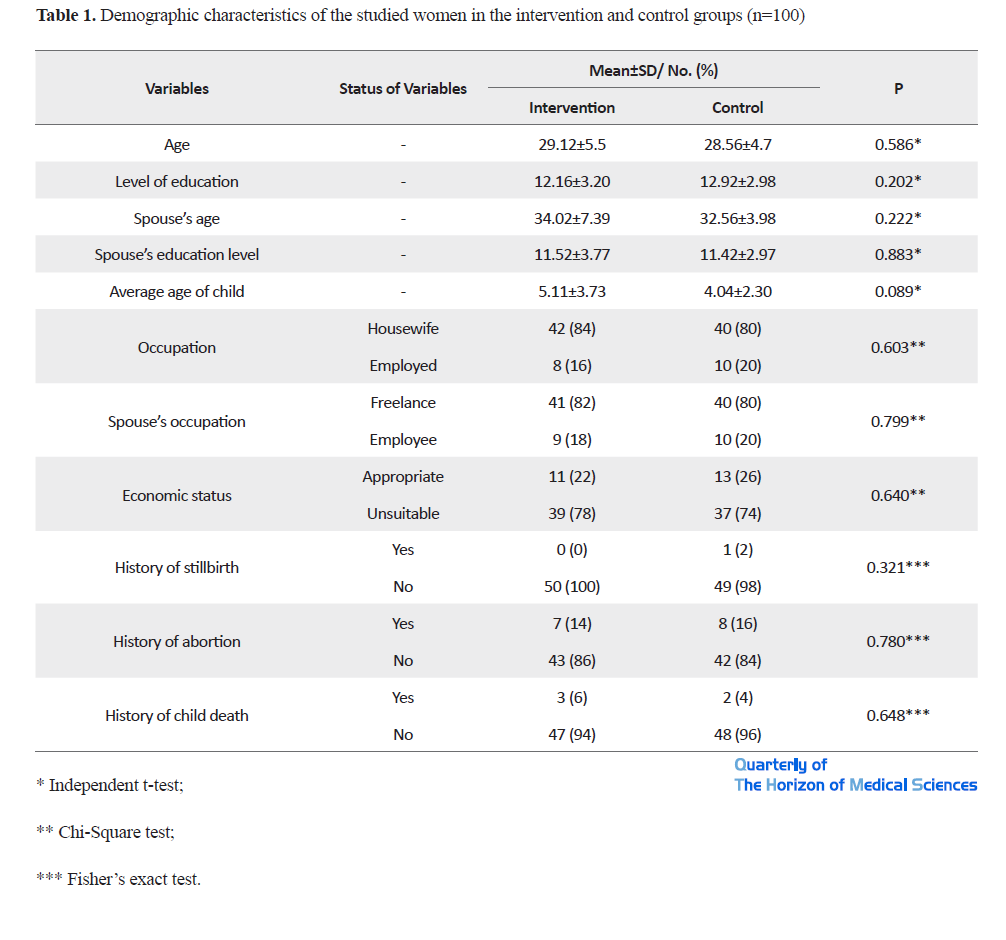

Based on the results, the mean age and years of education of the participants were 28.84±5.1 and 12.54±2.98 years, respectively. The mean age of the participants’ spouses and their years of education were 33.29±5.95 and t 11.47 38±3.38 years, respectively. On the other hand, there was not a statistically significant difference in terms of demographic characteristics, such as education level, employment, etc. between the two groups before the intervention (Table 1).

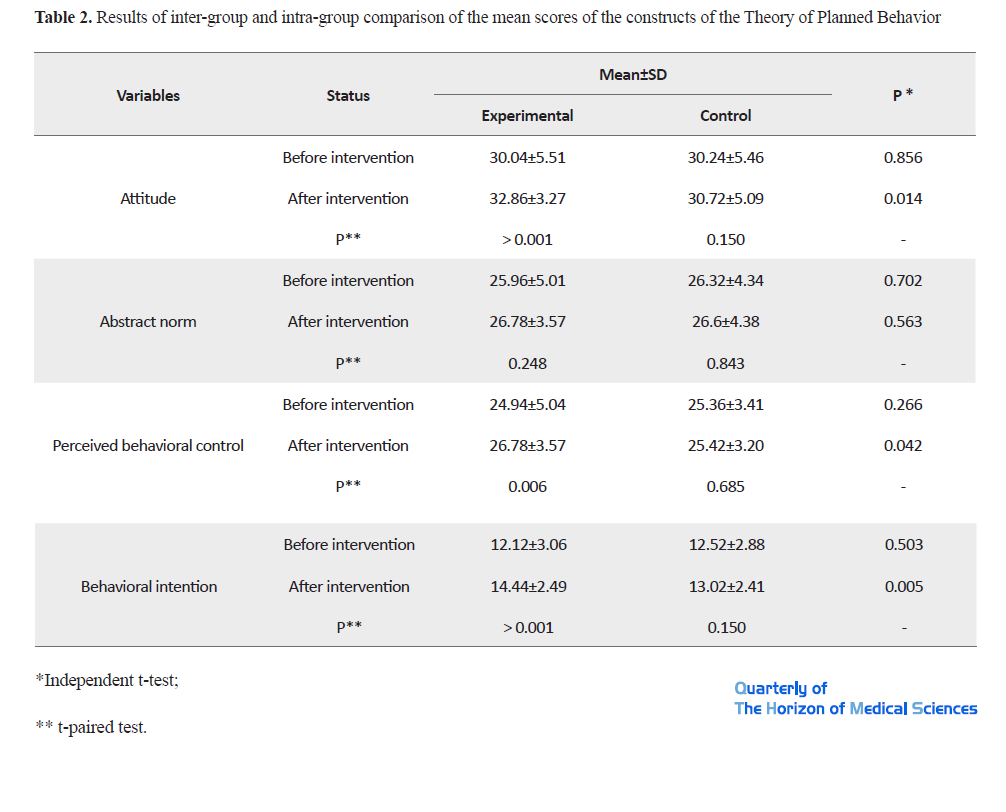

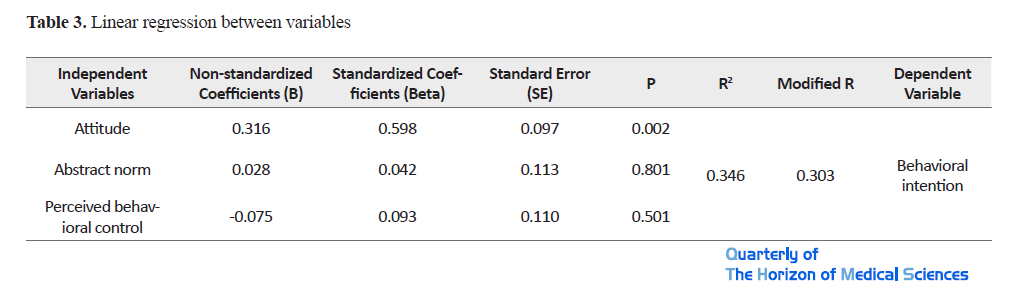

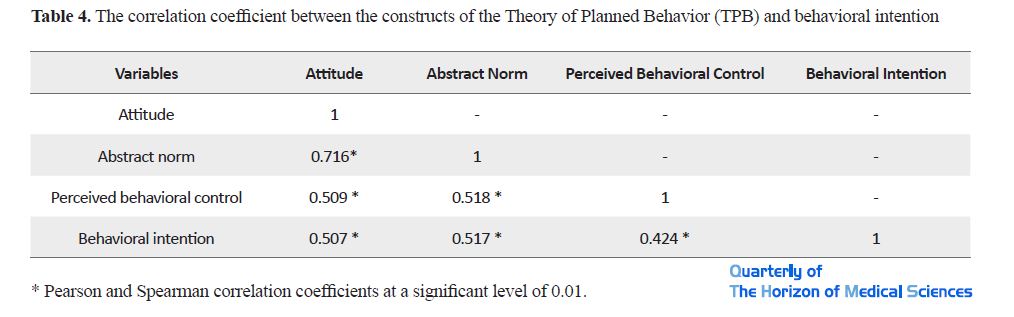

Tables 2, 3 and 4 indicate the prediction of behavior based on TPB using regression and how to examine its assumptions.

Accordingly, the Independent t-test, paired t-test, and chi-square test at a significance level of 0.05 and the Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients at a significance level of 0.01 were used for analysis.

Then, the linear regression showed that all constructs of the theory predicted 34.6% of the behavioral intention.

The attitude had more predictive power than other constructs (B=0.316). Based on the results of the Pearson correlation coefficient, the abstract norm showed the highest correlation, and the perceived behavioral control had the least correlation with the intention.

The aim of this study was to determine the effect of a TPB-based intervention on the intention of the fertility of the one-child families. The results showed that after performing the educational intervention, the mean score of attitude, perceived behavioral control, and behavioral intention in the experimental group was significantly higher than the control group, while regarding the abstract norm construct, no significant difference was observed between the mean scores of the two groups.

4. Discussion

Several cross-sectional studies have been conducted on fertility [3, 4, 6, 7], in which the effect of attitude on fertility intentions has been reported. The results of a study by Danielak et al. using an online intervention to measure the impact of fertility education on 199 men and women without children aged 18-35 years showed an increase in post-training attitudes, which is consistent with the present study [13]. The results of the present study showed a significant increase in the score of women in the experimental group regarding the intention to fertilize after the training program, which is consistent with similar studies conducted on TPB-based education, such as studies by Hosseini [14] and Ahmadi [15].

In this study, the perceived behavioral control significantly increased in the experimental group after the intervention, which is in line with the results of studies by Qiasvandy [16] and Jalmbadani [17], but not with the study by Delshad et al. [10]. This is due to the behavioral role of other family members in watching TV.

Also, there was a significant difference in the average score of behavioral intention construct after the educational intervention in both groups. Our results were consistent with the results of Williamson study [18], indicating that educating people about fertility had an impact on their reproductive intentions, as well as with the results of the study by Yekaninejad who showed that educational intervention based on TPB had a significant effect on the mean behavioral intention in the intervention group [19]. However, our results were inconsistent with the results reported by Ahmadi, who evaluated the effect of TPB-oriented education on the performance of breastfeeding first-born women [15].

In the present study, there was no significant difference in the mean score of abstract norm before and after the educational intervention in the experimental group, which was consistent with the results of studies by Sargazi [20] and Jalmbadani [17]. They reported no changes in the scores of the abstract norms after the education program in the intervention group compared with pre-education scores. However, it is inconsistent with the study by Shahraki-Sanavi [21], in which the abstract norms score in the experimental group increased after the educational intervention. This construct possibly indirectly affects behavior by affecting perceived behavioral control and attitude.

Since a person’s mental norms are influenced by important and key persons in his/her life, and in this study, no action has been taken to train key people, this could be the reason for the lack of a significant change in the experimental group. In this study, TPB constructs predicted only 34.6% of the behavioral intention; also, among the TPB constructs, the attitude had a higher predictor role. This result was consistent with the results of an intervention study based on TPB on the intention to use e-learning among faculty members [22], as well as Bellary et al. [23], Ashoogh [24], and Baghiani Moghaddam [25] studies, but is inconsistent with the results reported by Mehri to use seat belts based on TPB [26] and the findings of Dommermuth study entitled “Planned Behavior Theory And Fertility Realization” [27].

In this study, we used attitude as a predictor of fertility because individuals believe that the child facilitates or accelerates the achievement of their desired condition, which leads to a positive attitude in individuals to have children. Therefore, attitude should be considered as an important construct in educational interventions and measures related to promoting women’s intention to reproduction.

The present study had strengths and limitations. Being a community-based study, using health education models in the educational intervention, and sampling, allocating, and tracking the subjects can be cited as strengths of this study. One of the limitations of this study was the lack of an intervention to train key people, such as parents, spouses, and friends. Accordingly, it is recommended that future studies be conducted on groups that affect women’s fertility. The results of the present study can be used by reproductive health policymakers. In addition, our results provide the basis for future research and further studies in the application of other patterns and theories of health education and health promotion in reproductive behaviors.

5. Conclusion

According to Iran’s demographic policies and the findings of the present study, conducting educational interventions based on TPB and providing the required information to single-child spouses is effective on their intention to reproduce. It seems that the implementation of such interventions can be effective in the conscious decision of families to have children. On the other hand, the use of theoretical models and frameworks in the design of such educational interventions can increase their effectiveness. It can be said that by creating desirable mental attitudes and norms and higher perceived behavioral control, people can increase their intention to engage in a behavior; thus, the researchers propose implementation of this model in educational programs related to population growth policy and design of interventions to encourage couples at childbearing age.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of he Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences.

Funding

This study is the result of a MSc. thesis of Masomeh Esmailzade at the Health Education and Promotion, Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Health, Gonabad University of Medical Sciences (ID: REC 1393 130, GMU). The financial support of this research was provided by the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally in preparing all parts of the research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to all who helped us in this research, including all women who participated in the study, the officials and personnel of the community health centers, including the City Community Health Center No. 3 and the Community Health Center in Shahid Fayyaz district of Gonabad City.

References

1.Kaboudi M, Ramezankhani A, Manouchehri H, Hajizadeh E, Haghi M. [The decision-making process of childbearing: A qualitative study (Persian)]. Journal of the Iranian Institute for Health Sciences Research. 2013; 12(5):505-15. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=326182

2.Khadivzadeh T, Arghavani E, Shakeri M. [Attitude toward governmental incentives on childbearing and its relationship with fertility preferences in couples attending premarital counseling clinic in health centers in Mashhad (Persian)]. Journal of University of Medical Sciences 2015; 24(120):1-13.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281887101_Attitude_toward_governmental_incentives_on_childbearing_and

_its_relationship_with_fertility_preferences_in_couples_attending_premarital_counseling_clinic_in_health_centers_in_mashhad

3.Adibi Sedeh M, Arjmand Siahpoush E, Darvishzadeh Z. [The Investigation of Fertility Increase and Effective Factors on it among the Kord Clan in Andimeshk (Persian)]. Journal of Iranian Social Development Studies. 2012;4(1):81-94. http://jisds.srbiau.ac.ir/article_1916.html

4.Khadivzadeh T, Arghavani E, SHakeri M. [Determination association childbearing motivations with fertility preferences (Persian)]. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology University of Medical Sciences Mashhad. 2014; 17(114):8-18.

http://ijogi.mums.ac.ir/article_3414_afc52df01610ce305f6c756f27669800.pdf

5.Hosseini G, Hosseini H. [Comparing determinants of fertility behaviour among kurdish women living in rural areas of Ravansar and Gilangharb cities (Persian)]. Journal of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. 2013; 17(5):316-24. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Comparing-determinants-of-fertility-behaviour-among-Hosseini-Hosseini/edea30a512f040e564a00210596d3fe8a7094339

6.Hosseini H, Begi B. [Determinants of economic, social, cultural and demographic tendencies of childbearing women in Hamedan (Persian)]. Monthly Journal of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. 2014; 18(1):35-43. https://www.sid.ir/fa/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=223973

7.Keshavarz Mozafari H, Sharifirad G. [An Investigation on socio-demographic factors influencing on fertility rate in Shahreza (Persian)]. Journal of Health System Research. 2014; 10(1):66-76. https://www.magiran.com/paper/1278987/?lang=en

8.Modiri F, Ghazi Tabatabai M. The effect of quality of marital life on intention of childbearing. Sociology of Social Institutions. 2018; 5(12):73-94. http://ensani.ir/file/download/article/1559370529-10069-12-3.pdf

9.Baghianimoghadam HM, Fattahi Ardakani M, Akhondi M, Mortazavizadeh MR. [Intention of colorectal cancer patientsfirst degree relatives to screening based on pblanned behavior theory (Persian)]. Journal of Faculty Health Yazd. 2011; 10(3-4):13-22. http://tbj.ssu.ac.ir/browse.php?a_id=1795&sid=1&slc_lang=en

10.Delshad Noghabi A, Darabi F, Moshki M. [The impact of education on the basis of the theory of planned behavior on the level and method of supervision of their parents on watching television by students (Persian)]. Journal of Torbat Heydariyeh University of Medical Sciences. 2014; 1(4):7-17. http://jms.thums.ac.ir/article-1-58-fa.html

11.Hassanzadeh Rangi N, Allahyari T, Khosravi Y, Zaeri F, Saremi M. [Development of an occupational cognitive failure questionnaire: Evaluation validity and reliability (Persian)]. Journal of Iran Occupational Health. 2012; 9(1):29-40. http://ioh.iums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_id=708&sid=1&slc_lang=en

12.Hyrkäs K, Appelqvist-Schmidlechner K, Oksa L. Validating an instrument for clinical supervision using an expert panel. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2003; 40(6):619-25. [DOI:10.1016/S0020-7489(03)00036-1]

13.Daniluk J, Koert E. Childless canadian men’s and women’s childbearing intentions, attitudes towards and willingness to use assisted human reproduction. Human Reproduction. 2012; 27(8):2405-12. [DOI:10.1093/humrep/des190] [PMID]

14.Hoseini Soorand A, Miri MR, Sharifzadeh G. [Effect of curriculum based on theory of planned behavior, on components of theory in patients with hypertension (Persian)]. Journal of Birjand University of Medical Sciences. 2015; 22(3):199-208. http://journal.bums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_id=1778&sid=1&slc_lang=en

15.Ahmadi M, Jahanara S, Moein B, Nasiri M. [Impact of educational program based on the theory of planned behavior on primiparous pregnant women’s knowledge and behaviors regarding breast feeding (Persian)]. Journal of health. 2014; 16(1-2):19-31. http://hcjournal.arums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_id=238&sid=1&slc_lang=en

16.Gheysvandi E, Eftekhar Ardebili H, Azam K, Azadbakht M, Babazadeh T, Fathizadeh S. [Effect of an educational intervention based on the theory of planned behavior on milk and dairy products consumption by girl-pupils (Persian)]. Journal of School of Public Health and Institute of Public Health Research. 2015; 13(2):45-54. https://sjsph.tums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_id=5265&sid=1&slc_lang=en

17.Jalambadani Z, Shojaei Zadeh D, Hoseini M, Sadeghi R. [The effect of education for iron consumption based on the theory of planned behavior in pregnant women in Mashhad (Persian)]. Journal of Clinical Nursing and Midwifery. 2015; 4(2):59-68. http://jcnm.skums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_code=A-10-241-1&slc_lang=en&sid=1

18.Williamson LE, Lawson KL, Downe PJ, Pierson RA. Informed reproductive decision-making: The impact of providing fertility information on fertility knowledge and intentions to delay childbearing. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 2014; 36(5):400-5. [DOI:10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30585-5]

19.Yekaninejad M, Akaberi A, Pakpour A. [Factors associated with physical activity in adolescents in qazvin: an application of the theory of planned behavior (Persian)]. Journal of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences. 2012; 4(3):449-56. [DOI:10.29252/jnkums.4.3.449]

20.Sargazi M, Mohseni M, Safarnavadh M, Iranpor A, MirZaee M, Jahane E. [Eeffect educational intervention based on the theory of planned behavior leads to early detection of breast cancer in women referred to health centers in Zahedan (Persian)]. Journal of Breast Diseases Iran. 2014; 7(2):32-45. http://ijbd.ir/browse.php?a_id=342&sid=1&slc_lang=en

21.Shahraki Sanavi F, Navidian A, Rakhshani F, Ansari-Moghaddam A. [The effect of education on base the theory of planned behavior toward normal delivery in pregnant women with intention elective cesarean (Persian)]. Bimonthly Journal of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences. 2014; 17(6):531-9. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=385574

22.Bashirian S, Jalilian F, Barati M, Ghafari A. [A study on the predicting factors of intended e-learning among faculty members based on theory of planned behavior (Persian)]. Journal of Medical Education. 2014; 7(15):10-21. https://www.sid.ir/en/Journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=407961

23.Billari FC, Philipov D, Testa MR. Attitudes, norms and perceived behavioural control: Explaining fertility intentions in Bulgaria. European Journal of Population. 2009; 25(4):439-65. [DOI:10.1007/s10680-009-9187-9]

24.Ashoogh M, Aghamolaei T, Ghanbarnejad A, Tajvar A. [Utilizing the theory of planned behavior to prediction the safety driving behaviors in truck drivers in Bandar Abbas (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Health Education and Health Promotion. 2013; 1(3):5-14. http://journal.ihepsa.ir/browse.php?a_code=A-10-73-1&sid=1&slc_lang=en

25.Baghianimoghadam M, Gholianavval M, Karimi M, Kamalikhah T, RoohiMoghadam R. [Investigating the views of male students on using bicycles based on the theory of planned behavior in yazd university of medical sciences (Persian)]. Journal of Research Colledge Yazd. 2013; 13(4):83-94. https://www.sid.ir/en/Journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=419280

26.Mehri A, Sedighi Somea Koochak Z. [Application and comparison of the theories of health belief model and planned behavior in determining the predictive factors associated with seat belt use among drivers in Sabzevar (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Medical Education. 2012; 11(7):806-18. http://ijme.mui.ac.ir/browse.php?a_id=1318&sid=1&slc_lang=en

27.Dommermuth L, Klobas JE, Lappegård T. The theory of planned behavior and the realization of fertility intentions. Advances in Life Course Research. 2011; 16(1):42-53. [DOI:10.1016/j.alcr.2011.01.002]

Received: 2019/01/15 | Accepted: 2020/04/7 | Published: 2020/06/21

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |